I have been a very lucky lady. A few weeks ago I was offered a place on a trip to Romania for a Green Village Project, organised by Grampus Heritage and Training Ltd. They specialise in European projects, involving a number of countries, demonstrating, exchanging and collaborating traditional cultures, crafts and skills.

It was set around a remote village close to Auid, Transylvania. The village is quite remarkable, for an ill-informed Londoner like myself. Almost every part of the function and survival of the village, the surrounding land and the residents, is sustained within their land. During our 4 day stay there we only ate vegetables grown by the host, Monica's grandmother, sausages and smoked meat from their pigs, eggs from their many chickens, wine and grappa from their grapes, water from their well, bread from their flour, pickles from their own vinegar, the list goes on. Lunchtimes were banquets of typical village food - all naturally delicious, and 100% organic.

However, we had to work for our lunch, the real reason the project was there, to build a traditional green fence strong enough to keep huge wild pigs off the potato patch. Using only one chainsaw and a horse and cart a few of us wandered up through the vast orchard (planted by the co-operatives of the Communist rule. When land and property was finally returned to their rightful owners there was a lot of work to be done by individuals, so some became neglected and left to ruin - like this orchard) to the woods and collected young trees no thicker than 2 inches. Back at the potato patch green poles were striped of their bark and spaced evenly. Removing the bark allowed the young trees to slide along the poles when they are weaved and pushed down.

Working with at least two young trees at a time, the weaving begins in a systematic way, always starting on one side and moving along one pole as you add. On the next row you start on the other side. Once a substantial 'base' has been created the trees are stabbed in the weave close to a pole and bent down, filling in any gaps or thin areas. It's definitely a two man job. The locals were full steam ahead and jibber-jabbered away in Romanian (fuelled with grappa) so I just stepped aside and admired the speed they worked at. Jumping on top of the weave to flatten it down seemed vaguely helpful, sometimes.

The finished product was beautiful, cheap and so strong, using all my weight it didn't rock at all. This years potato harvest is going to be a good one!

So, can we look to these people's example and see a sustainable future? This was the question I set out to answer on my travels via the metropolis of Manchester. I conclude not really. Our global society would not and should not step back to an almost medieval existence. However, there are things that make sense which needs to be echoed the world over. Firstly the understanding of how and where our food and resources come from.

If you appreciate the real cost or effort of growing a potato harvest fit to feed your family for the year ahead then I believe there would be a dramatic change in the amount of waste. A change that I think will echo in purchasing and consumption. This family rinse scraps from their pots and plates in a little bit of water to feed the dogs which guard their home. The chicken poo is collected and fertilises the potatoes. Everything has a use. In London we may not all have chickens, cows and a garden big enough to grow our veg, but we do waste food like it doesn't matter - that's from the disconnection. I wonder what a difference community compost heaps could make.

Another lesson to be learned is the use of the materials and resources we have to hand. Discounting the chainsaw fuel, labour and grappa, the material for our green fence was essentially free. The trees selected were the right size but also removed to thin out the woodland, something which every woodland needs for it to develop into a healthy ecosystem that can become a benefit environmentally and commercially. In England our wood product is practically a waste product of recreational programmes within our National Woodlands. There have been incentives and grants set to encourage people to plant trees but the important emphasis on what and how to use these new woodlands is dying out. Simultaneously industry has either replaced varied hardwood woodland for fast growing softwoods or extensively imported from as far as New Zealand. I can see a catalyst for change happening from a creative look at what we need and how it can be provided for by what we have already.

The first thing that grabbed me as we drove into the village for the first time was the strange, alien-like trees dotted around the landscape. The ancient art of pollarding and coppicing Willow is clearly still widely practiced, and as I found out, vital to everyday life. Here at home, we have hundreds of years history of coppiced woodland. Aside from being beautiful homes to all varieties of insects, birds, mammals and wild flowers they provided firewood, food and materials. Once you coppice you realise how resilient and amazing trees are. The more you hack at it the more it'll grow back; three times more shoots for you to harvest and use next year. Once upon a time all of our necessary materials came from what we had around us. I have begun to really ponder on the realities of a fresh look at this tradition for some of our needs today.

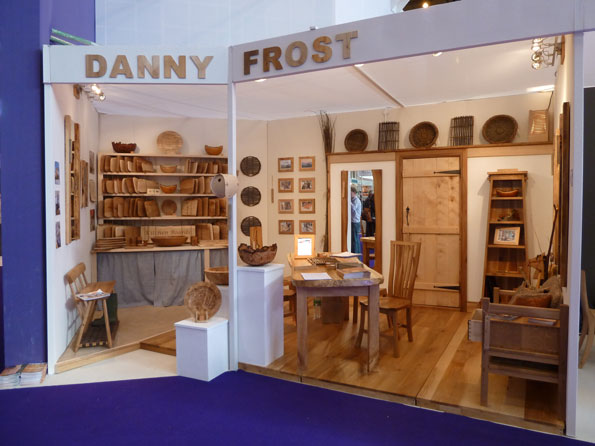

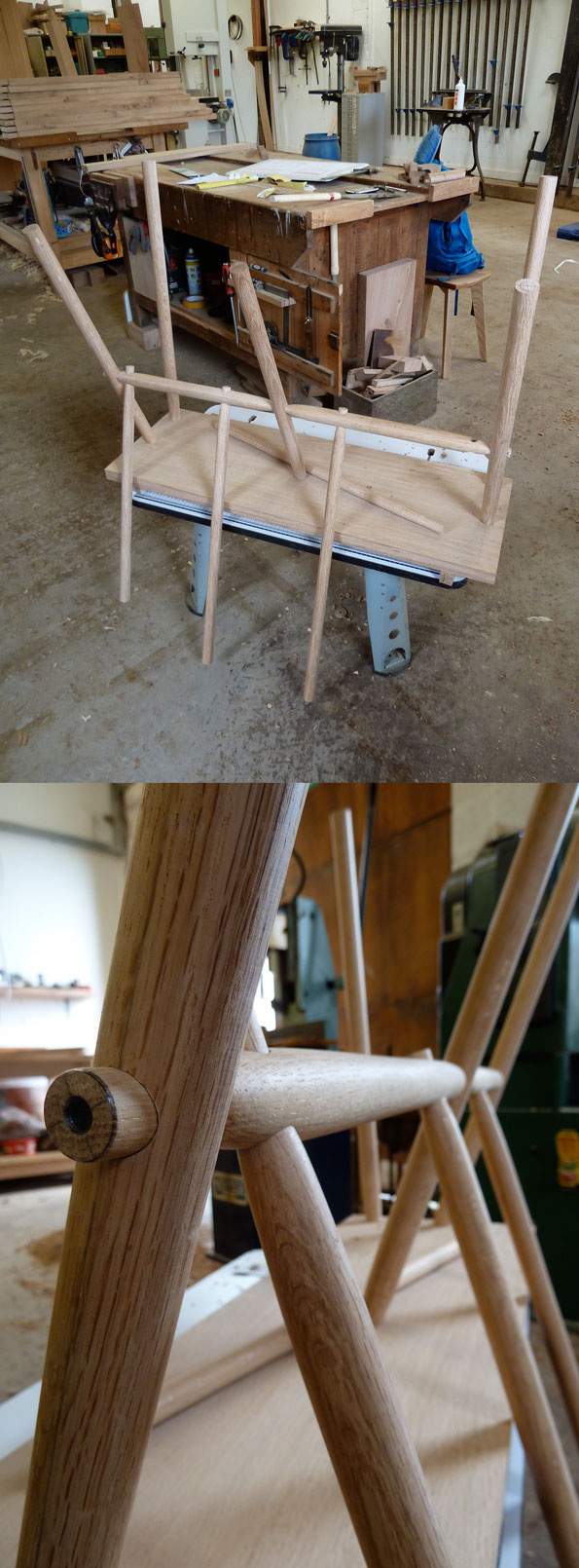

Finally, I must touch on the pros and cons of 'Working with your hands vs. Working with machines'. It's an age old debate and many people, including the Arts and Crafty lot 100 years ago, have approached it far better than I ever could. The point I will highlight though: the debate is still happening and still as important. The reason why this Romanian village is beginning to struggle is the fact that the young people are moving to the cities to find work. Tending the land by hand just does not pay. The orchard has been left to waste because it would take a huge, fit team to prune and harvest it every year. The price of food has dropped because of the use of machinery, for organic hand grown produce to compete just isn't viable. I visited the market where all the local farmers trade and swap their spoils, these people know and understand when and how food grows, so they know not to buy things out of season, why? because otherwise it doesn't taste as good, simple as that. Back in the UK we've lost that and prioritise cheap and all-year round convenience over flavour and nutrition. Looking at these big issues through the food market is helpful. It encapsulates what the consequences of industrial trends are because it's an everyday need. The product and furniture market roughly follows the same story, with a few extra things thrown in. The machine has opened up so much to so many people, which is a good thing, for the short term. We are at an advantage point, where everyone (in the UK) has access to their basic needs, from here we can begin to plough forward with long sighted vision. The slow food and organic movement started from a change of attitude of the buyer. People began to demand better because it's better for them in the long run. Can this not become the big trend of the mid-twenty first century?

Finally, I must touch on the pros and cons of 'Working with your hands vs. Working with machines'. It's an age old debate and many people, including the Arts and Crafty lot 100 years ago, have approached it far better than I ever could. The point I will highlight though: the debate is still happening and still as important. The reason why this Romanian village is beginning to struggle is the fact that the young people are moving to the cities to find work. Tending the land by hand just does not pay. The orchard has been left to waste because it would take a huge, fit team to prune and harvest it every year. The price of food has dropped because of the use of machinery, for organic hand grown produce to compete just isn't viable. I visited the market where all the local farmers trade and swap their spoils, these people know and understand when and how food grows, so they know not to buy things out of season, why? because otherwise it doesn't taste as good, simple as that. Back in the UK we've lost that and prioritise cheap and all-year round convenience over flavour and nutrition. Looking at these big issues through the food market is helpful. It encapsulates what the consequences of industrial trends are because it's an everyday need. The product and furniture market roughly follows the same story, with a few extra things thrown in. The machine has opened up so much to so many people, which is a good thing, for the short term. We are at an advantage point, where everyone (in the UK) has access to their basic needs, from here we can begin to plough forward with long sighted vision. The slow food and organic movement started from a change of attitude of the buyer. People began to demand better because it's better for them in the long run. Can this not become the big trend of the mid-twenty first century?